Despite taking up relatively little space, the story of Cain and Abel tends to be well known. Coming immediately after Adam and Eve are ejected from Paradise, the story of the two brothers occupies a single chapter of Genesis. It provides a bridge into an explanation of how humanity spread beyond the First Family, and starts the story of the Third Fall of Man (the one that leads to the Flood).

As well as the story of the first birth and the first murder, chapter 4 of Genesis is notable for including several other firsts:

- The founding of the first city

- The ancestor of all nomads and farmers

- The ancestor of all musicians

- The first metal-worker

As an aside; this story also appears in the Qur’an where it contains another first not mentioned in the Old Testament. In 5:31 it is mentioned that God sent a raven to scratch up the ground and show him how to hide Abel’s corpse. I.e., the first burial.

Genesis 4

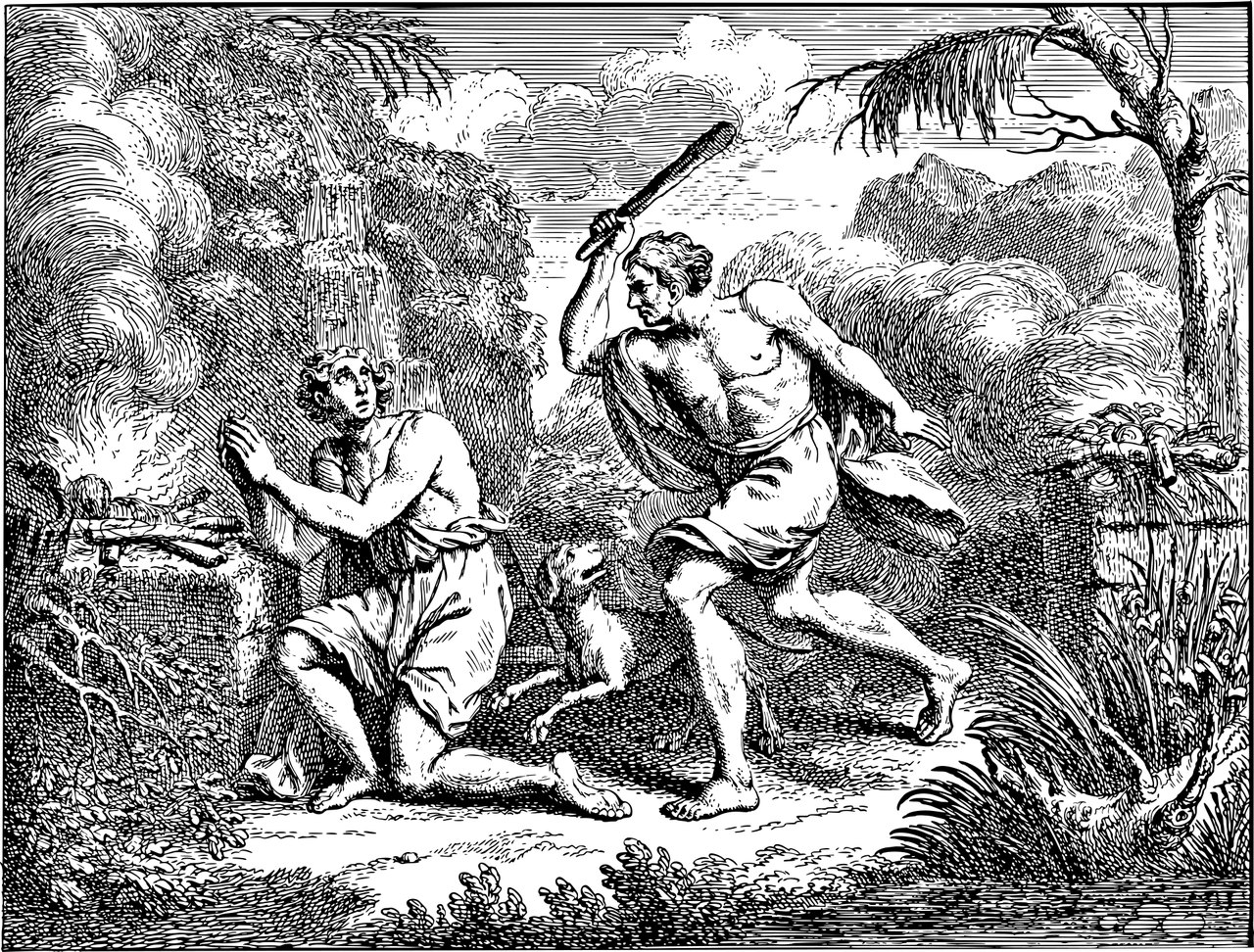

The story of Cain and Abel is relatively short. Cain, the elder brother, farmed crops, while Abel, the younger brother, farmed livestock. Each of them offered some of his own produce to God. Unfortunately God was not at all impressed by Cain’s offering. In a fit of rage due to this rejection Cain lured his brother into a field to kill him.

After initially denying it, a direct question by God leads him to confess. God curses him so that he will no longer be able to grow crops. Realising the enormity of what he has done, Cain cries out that he will be hunted and killed by whoever meets him. God then marks him to warn people that killing Cain will bring a seven-fold vengeance.

Cain then wanders off to the Land of Nod where he marries, has children, and founds a city. It is Cain’s descendants — the inhabitants of this city — that provide all the “firsts” listed above.

Treatise on the Reintegration of Beings

Much can be made of this, but here we are interested in the interpretation of Martinés de Pasqually in his famous “Treatise on the Reintegration of Beings.“

In this work, Pasqually goes through his own interpretations of the stories of Genesis. He highlights the stories of eleven different individuals, with the first being, unsurprisingly, Adam. The second and third characters that he covers are Cain and Abel.

He manages to take this relatively short story of roughly sixteen verses (if we ignore the founding of the city and the “firsts”) and turn it into a symbolic narrative of nineteen pages (in my English translation). While the basics of the story remain the same, Pasqually expands the cast of characters, adding two sisters that were born after Cain but before Abel, and considerably develops the story to add to the drama and symbolism of the fateful event.

Adam and Eve in materiality

In Pasqually’s tale, Cain and his sisters Kani and Abac, are doomed from the start. They are born from an act of furious material passion (*cough*) that goes against the intention of God’s command to “be fruitful and multiply”. This excessive materiality extends the period that Adam has to work for his own reconciliation and curses these children to perform acts that will also have profound implications for all of subsequent humanity. Abel on the other hand is born from a “pure and simple conception without excessive participation of their material senses”, and so becomes a child of peace.

Pasqually takes the time to draw explicit connections with events from the birth of Christ. He points out parallels between Adam and Eve on one hand, Elizabeth and Zacharias on the other and Mary and Joseph. Also mentioned is the Christ-like perfection of Abel, with explicit discussion not only of his wise and virtuous behaviour, but also his constant devotion to the Creator.

The trigger for Cain’s murderous rage is significantly different in Pasqually’s re-telling. He describes a magical act involving the three men of the family — Adam, Cain, and Abel. Adam chooses Abel to draw the circles and prepare the magical space, consecrating him appropriately for this. Later in this working, Adam and Abel swap positions so as to allow the younger son to also enjoy direct communication with the Divine. Cain is not completely forgotten, but is blessed by Adam only at the end of the ritual with a wish that his “future works be like those of your younger brother”.

A magical crime

All of this is interpreted by Cain as an enormous insult. Since he is the older brother, he believes that his birthright has been stolen and he says as much to his sisters. They then rile him up and encourage him to use his own power against his father and brother, and even against the Creator who allowed all of this. Cain performs an identical ceremony with his sisters, allowing them to serve in the roles originally taken by Adam and Abel. At the nadir of this evil ceremony, he offers the body and soul of his brother to the prince of demons. In this, Pasqually adds to Black Magic to the list of “firsts”.

Abel, in his Christ-like perfection, knows what is coming. He takes time to explain to his brother that this evil ritual was a crime even greater than that of his father. He tries to console Adam, who also appears to know what will happen next. Presaging the remainder of his Treatise, he has Abel explain to Adam that the Creator will deliberately place key people — prophets — into history as His tools.

Visiting one another, the two sisters embrace their father and Cain embraces Abel. Much like Judas will later use a kiss as a weapon against Christ, Cain uses the embrace to stab Abel three times with a wooden dagger (remember that the metal-worker Tubal-Cain had not yet been born). Once in the throat, once in the heart, and once in the stomach (Freemasons take note!).

This forms the basic outline of the story as presented by Pasqually. The remainder of the text is spent expanding on the ideas he introduced, and linking it with his numerological system. As a footnote to the story he explains how Cain is later accidentally killed by his son Boaz in a hunting accident. Boaz is then forced to withdraw from the city in order to escape the revenge of Cain’s descendants.

Narrative Dogmatism

The question that first struck me is how Pasqually can have taken it upon himself to spin so many details out of the short chapter in Genesis. He states everything in his version as if it is undeniably true, but never gives a justification for this. Much of this is due to his style — my initiator has described Pasqually as a “narrative dogmatist” rather than a philosopher. But it is not entirely without precedent.

If your bible contains what Protestants might refer to as “The Apocrypha”, you can turn to chapter 10 of the Wisdom of Solomon (sometimes referred to as The Book of Wisdom.)

Wisdom protected the first-formed father of the world, when he alone had been created; she delivered him from his transgression, and gave him strength to rule all things. But when an unrighteous man departed from her in his anger, he perished because in rage he killed his brother. When the earth was flooded because of him, wisdom again saved it, steering the righteous man by a paltry piece of wood.

“Wisdom of Solomon”, 10:1-4

While this is clearly very far from Pasqually in the amount added to the original story, it does add hit on several of the points he discusses. In particular, the fact that Adam was, in fact, delivered from his sin (a detail mentioned nowhere in Genesis), and the idea that the pollution of the earth that required the Flood was directly due to Cain.

This chapter of the Wisdom of Solomon continues in a way that is very similar to Pasqually. That is, it goes through many of the key characters from Genesis and draws spiritual lessons from their stories. Pasqually likes to tie these lessons to his own system, whereas the Wisdom of Solomon connects these to the actions of Wisdom herself, but the idea is the same: the identification of key characters in the mythological history of humanity that serve to illustrate our daily spiritual journeys.

What to make of this?

Firstly, Pasqually is not alone in freely interpreting biblical stories in this way. The Wisdom of Solomon — which also does the same sort of free interpretation — is accepted as canon by a majority of the world’s Christians. Pasqually may be going far beyond the intent of the original author, but he stands in a venerable tradition of bending biblical texts to his own will.

Secondly, Pasqually’s spiritual mythology contains many Fall-Redemption cycles, with some of these cycles living (like fractals?) within others.

The Fallen First-Spirits could not be redeemed within Time, and so Adam was sent to rule the material world created as a prison for these spirits. Emanated “after” them (whatever that word may mean outside of Time), he was specified as their superior and elder — much like Adam consecrated the younger son Abel to act in the role of the elder during their magical rite. The redeemed-Adam (redeemed by the creation and birth of Abel) thus acted in a God-like role to bring forth a Holy Magician who could act within the material world.

The pride of the material being (Cain) could not allow such a thing, and so he sought to destroy this Magician. But by doing so he cursed himself and all of subsequent humanity. Pasqually describes Cain’s various actions alternately as worse than Adam’s original crime:

…you have just performed a false and impious act of worship before the Eternal. The extent of your crime surpasses Adam’s, and you have wrongly sought to shed the blood of the righteous for the justification of the guilty.

…and as less:

…is no more a criminal than Adam was towards the Creator. Cain only struck matter, but Adam took God’s throne by force; see which is the more criminal!

Symbolic axes

There are a few different axes at work in all of this. Beyond the simple Good<->Bad axis, there is the Elder<->Younger and/or Superior<->Inferior relationship of Cain to Abel, Humanity to the Creator, Adam to the Fallen First-Spirits, etc.

The description of the two magical acts (the first by Adam, Abel, and Cain, and the second by Cain and his sisters) also shows that these lie along an axis. That is, apparently identical magical acts exist on a spectrum of Holy to Diabolical.

Additionally, the character of Cain describes our actions as “Men of the Stream”, as Louis Claude de Saint Martin would say, while Abel clearly prefigures Christ. That is, wallowing in materiality to rising above it into the Real.

Redemption requires its own Fall

He describes Abel’s murder as tragically necessary for the redemption of Adam and Eve, while cursing their descendants until the end of time. A “spiritual interpreter” answers the prayers of Adam and Eve and explains to them that their creation of both Cain and Abel allowed for their reconciliation and forgiveness. Abel’s spiritual descendants are the prophets and guides that will appear throughout history to steer mankind back to the Truth, and Cain’s actions will serve forever as an example of the actions of the “perverse spirits”.

Tragedy is a fundamental aspect of the cosmology presented by Pasqually. The emanation of the God-Man Adam required the catastrophe of the Fall of the First Spirits. Adam’s Free Will, which was absolutely necessary for his mission, directly led to his own Fall, and his own redemption required the creation of adversarial brothers and the introduction of murder into the material world.

The Great Work is never done

In Pasqually’s view, the Material is not the Real. We reach the Real through redemptive acts involving the creation and manipulation of symbolic truths. These truths lead to a tragic continuation of Fall-Redemption cycles, with each subsequent generation of symbolism needing to go through the work of its own redemption.

The work implied by our Fall is never done. Our redemption leads to further symbolic crimes, each of which needing the actions of the Creator. Through this work we emerge from the Stream, moving steadily towards the Light, and allowing Holy Wisdom to spread Her light throughout our Being.

Do not stop working.

Find the Redemption in each Fall.

Allow Holy Sophia to spread Her Light within you.

Before the Flambeaux.

Leave a Reply